High haemoglobin and haematocrit: real risk vs gym myth

How dangerous is it, what markers to look for and how your body can reset to higher levels

By Gary Chappell

FOR years the bodybuilding world has talked about “danger thresholds”, “ticking time bombs” and imminent stroke risk whenever someone returns a high haemoglobin and haematocrit result.

But what does the medical evidence actually say? And how should athletes interpret elevated numbers without falling into fear-based thinking?

This article breaks down what raised haemoglobin (Hb) and haematocrit (HCT) really mean, what doctors are genuinely concerned about, the role of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) and anabolic steroid use and, most importantly, what the actual risks are according to medical evidence.

What are haemoglobin and haematocrit?

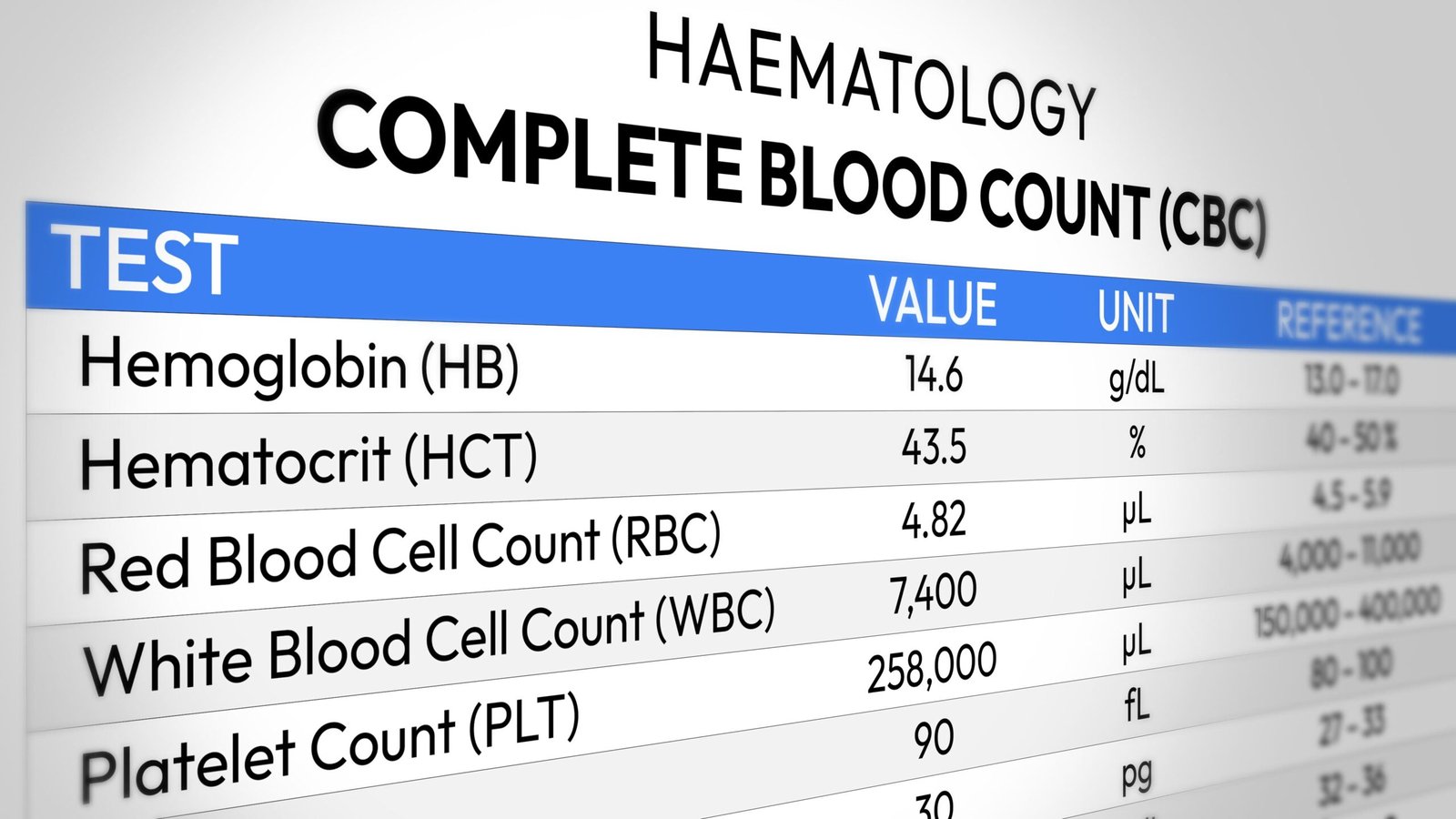

Hb) and HCT are two key values measured in a full blood count.

- Haemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying protein inside red blood cells.

- Haematocrit is the percentage of your blood volume made up of red blood cells.

Normal ranges vary slightly by laboratory but, in adult males, haemoglobin is typically around 135–175g/L, while haematocrit usually sits between 40–50 per cent. Values above these ranges are considered elevated. When both haemoglobin (Hb) and haematocrit (HCT) are raised, this is often referred to as erythrocytosis or polycythaemia.

Why haemoglobin and haematocrit become elevated

1 Primary erythrocytosis (polycythaemia vera)

This is a rare blood cancer in which the bone marrow produces excessive red blood cells, most commonly due to JAK2 mutations. It is usually accompanied by raised platelets and white blood cells and requires specialist haematology care.

2 Secondary erythrocytosis

This is far more common, particularly in athletes, and includes causes such as:

- Sleep apnea

- Chronic hypoxia

- Testosterone or anabolic steroid use

- Smoking or high-altitude exposure

- Certain kidney or cardiac conditions

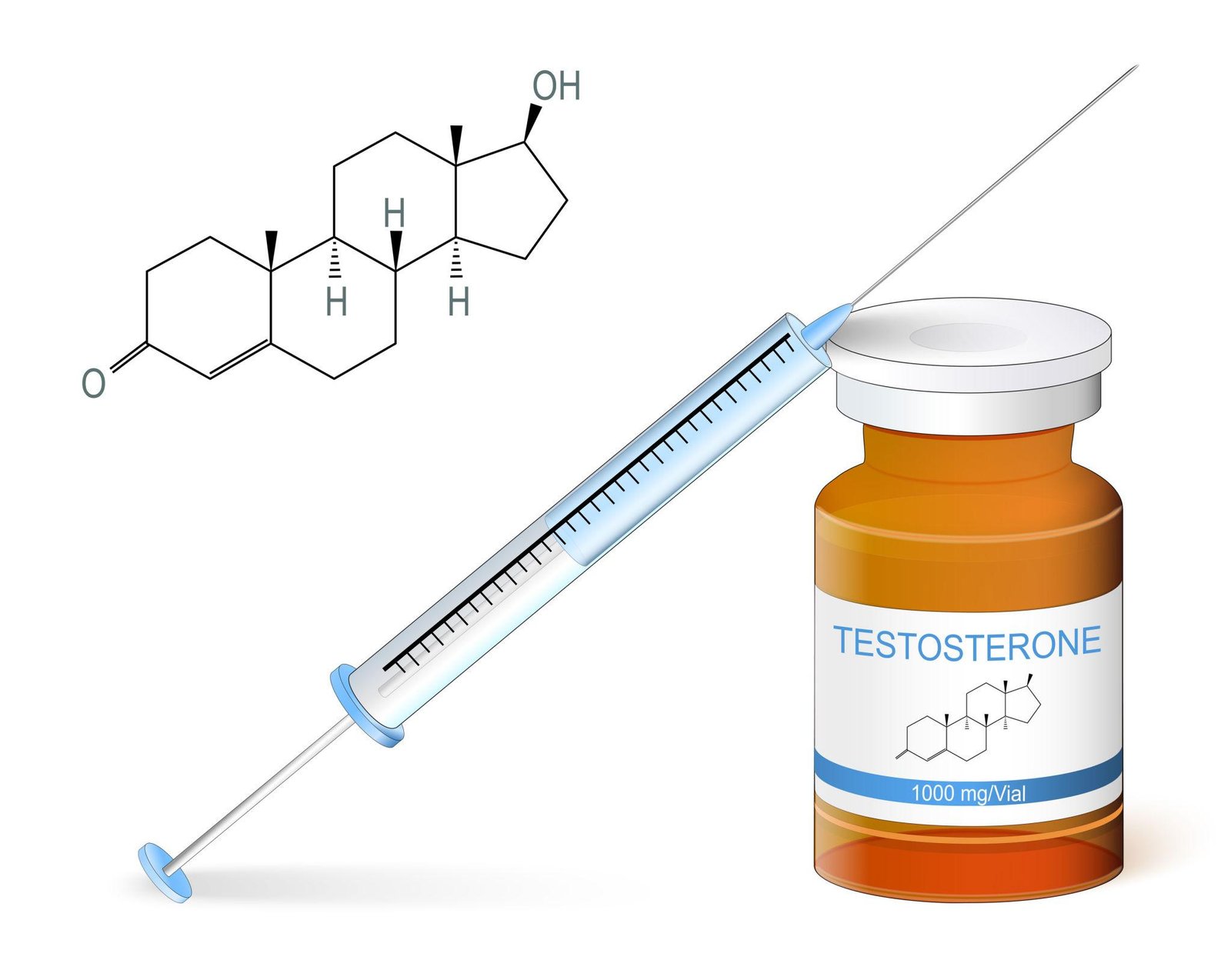

With testosterone or androgen use, red blood cell production is stimulated via increased erythropoietin signalling and altered iron metabolism. Medically, this is classified as secondary erythrocytosis.

What bodybuilders often get wrong

The typical gym narrative goes something like this: “High haematocrit means thick blood, which means a stroke is imminent.”

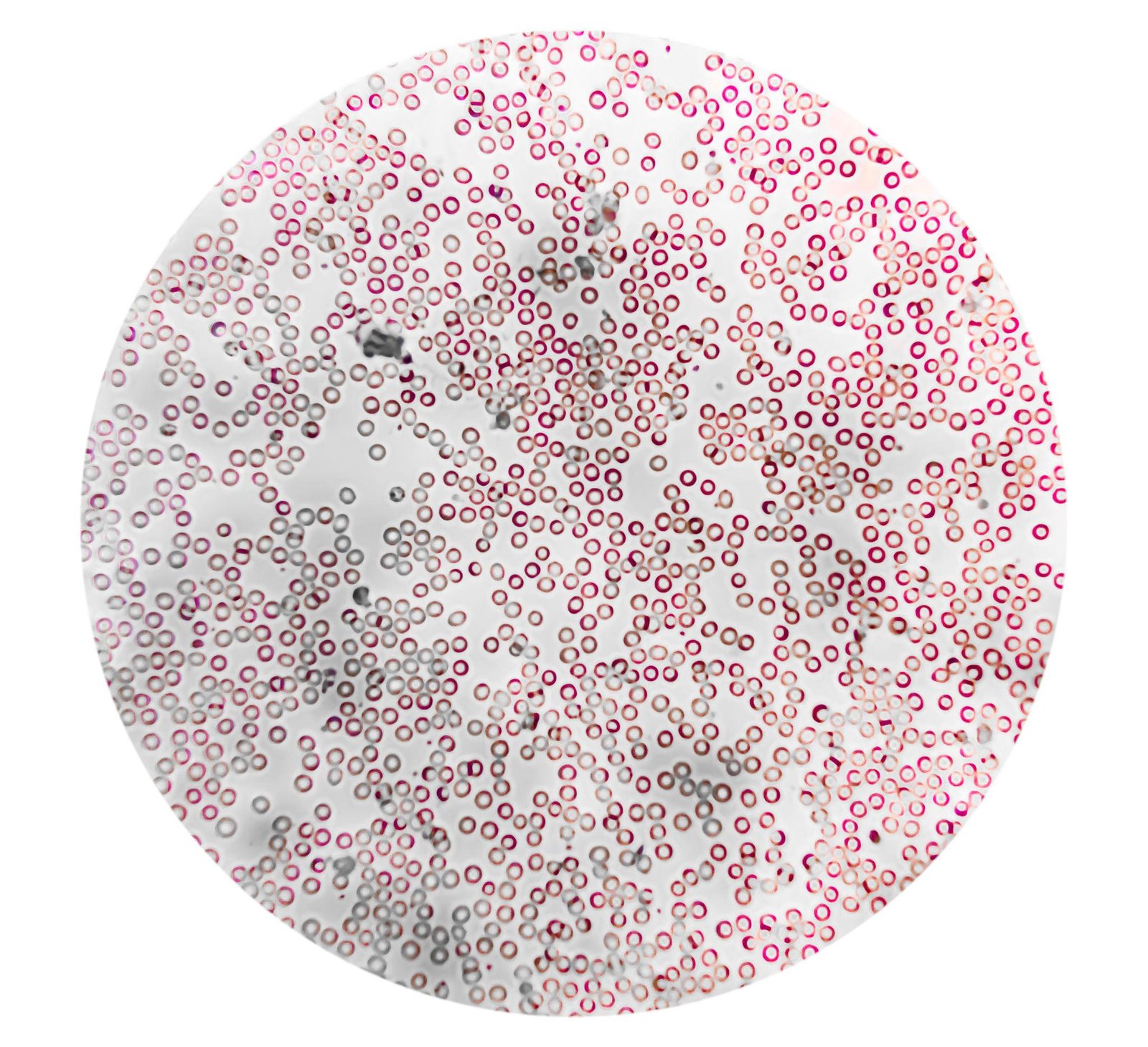

That is not how medicine works. Elevated Hb and HCT can increase blood viscosity, but blood viscosity alone does not guarantee clotting, stroke, heart attack or death. The relationship between red cell mass and thrombosis is complex and context-dependent.

In many forms of erythrocytosis, thrombosis risk is influenced by platelet and white-cell behaviour, not just red cell count Some inherited conditions show clot risk independent of haematocrit level. And in certain cases, repeated blood removal/letting (phlebotomy) has paradoxically increased clotting risk by disrupting blood dynamics

Put simply: haematocrit alone is not a reliable predictor of clotting events.

So is testosterone responsible? Yes, particularly injectable testosterone. Testosterone is one of the most common causes of secondary erythrocytosis. Multiple studies show that men using injectable testosterone have a significantly higher likelihood of elevated haematocrit compared with other formulations.

One clinical comparison found that about 33 per cent of men on injectable testosterone exceeded a haematocrit of 50 per cent. Another analysis reported that men receiving testosterone therapy had a 315 per cent higher likelihood of developing erythrocytosis compared with untreated controls.

This is a well-documented physiological effect, not speculation.

Does high haematocrit increase stroke or heart attack risk?

This is where gym lore diverges most sharply from evidence. Large population studies do show an association between higher haematocrit and increased cardiovascular or venous thromboembolic risk. However, these studies demonstrate association, not direct causation and many cannot fully control for smoking, obesity, hypertension or metabolic disease. In addition, most are not specific to athletes, bodybuilders or TRT patients

Even major clinical reviews conclude that, in secondary erythrocytosis, the independent contribution of elevated haematocrit to clot risk remains inconclusive.

In other words: elevated haematocrit is a risk modifier, not an automatic catastrophe.

Clinicians are less concerned with one isolated result and far more focused on patterns and context.

Key considerations include:

- Platelet count: High platelets raise suspicion of marrow disease or hypercoagulability

- White blood cell count: Elevation alongside red cells suggests primary pathology

- Trend over time: Stable elevation differs from progressive escalation

- Symptoms: Non-specific flushing or headaches are common; true red flags are clot symptoms

- Comorbidities: Hypertension, arrhythmias, smoking and heart disease compound risk

So is high haematocrit dangerous for bodybuilders?

It can be, particularly when combined with other risk factors. But it is not a “ticking time bomb” by default.

Clinical guidance (including NHS-aligned practice) treats persistent erythrocytosis as something to monitor and stratify, not an emergency unless accompanied by additional abnormalities or symptoms.

Typical clinical steps include:

- Excluding dehydration and relative causes

- Identifying secondary drivers such as hypoxia or hormones

- Ruling out polycythaemia vera where appropriate

- Adjusting medication or lifestyle factors

- Monitoring trends rather than reacting to one result

In secondary erythrocytosis, interventions such as dose adjustment or controlled phlebotomy are used to manage overall risk, not to chase arbitrary numbers.

Interestingly, the American practice guideline on testosterone therapy recommends against the use of testosterone in patients with hematocrit above 50 percent or untreated obstructive sleep apnea, whereas the European guideline on male hypogonadism suggests that testosterone therapy is contraindicated at a hematocrit greater than 54 per cent.

Why some athletes “reset” to a higher haemoglobin level

A frequently misunderstood phenomenon is why haemoglobin and haematocrit may remain elevated even after blood donation/letting or dose reduction. This is real physiology.

Red blood cell production is regulated primarily by the kidneys’ oxygen-sensing mechanisms. When oxygen delivery has been chronically challenged, through sleep apnea, large body mass, sustained androgen exposure, or prolonged high demand, the system adapts.

Over time, the body may defend a higher red cell mass as its new baseline, sometimes referred to clinically as a reset erythropoietic drive.

Once established, haemoglobin may rebound after venesection and levels may not normalise quickly after dose reduction.

Blood donation or letting removes red cells, but it does not alter the kidney’s oxygen-sensing logic. If the body perceives higher oxygen-carrying capacity as necessary, it will simply replace what was removed.

This rebound effect is expected in secondary erythrocytosis and is not evidence of cancer or loss of control. Crucially, a higher baseline does not automatically equal danger, but it does reduce margin for error, as we will discuss next.

When baseline haemoglobin is already elevated, stacking additional erythropoietic stimuli, dehydration, stimulants or aggressive contest-prep tactics carries disproportionately higher risk.

That does not mean progression or competition is impossible, but it does mean escalation comes at a higher physiological cost. That is risk management, not fear.

So elevated haemoglobin and haematocrit are signals, not sentences. They warrant interpretation, monitoring and medical context, not panic fuelled by social media and gym folklore.

What bodybuilders often call a “catastrophe waiting to happen” is more accurately described as:

A marker that deserves careful evaluation, trend monitoring and informed decision-making. Clarity beats fear. Evidence beats myth.

References:

- McMullin MFF, et al. A guideline for the management of specific situations in polycythaemia vera and secondary erythrocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2019.

- Fox S, et al. Polycythemia Vera: Rapid Evidence Review. Am Fam Physician. 2021.

- Marchioli R, et al. Cardiovascular Events and Intensity of Treatment in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV). N Engl J Med. 2013.

- Olivas-Martinez A, et al. Causes of erythrocytosis and its impact as a risk factor for thrombosis and mortality. Blood Res. 2021.

- Nguyen E, et al. Phenotypical differences and thrombosis rates in secondary erythrocytosis vs polycythaemia vera. Leukemia. 2021.

- Cervi A, et al. Testosterone use causing erythrocytosis. CMAJ. 2017.

- Bond P, et al. Testosterone therapy-induced erythrocytosis – can phlebotomy be justified? Endocr Connect. 2024.

- Kohn TP, et al. Rises in Haematocrit Are Associated With an Increased Risk of MACE in Men on Testosterone Therapy. J Urol. 2024.

- Neidhart A, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of testosterone-induced erythrocytosis. Front Endocrinol. 2025.

- McMullin MFF, et al. Diagnosis and management of polycythaemia vera. Br J Haematol. 2019.

- Martelli V, et al. Prevalence of elevated haemoglobin and haematocrit in OSA. Sleep Breath. 2022.

- Medscape. Secondary Polycythemia – Overview. Updated 2024.

Frontdouble's HEALTH AND EDUCATION HUB

Leave a Reply