THE debate over optimal training volume has been ongoing for decades. On one side, there are low-volume, high-intensity training (HIT) advocates who argue that brief but maximally intense sessions maximise muscle growth and recovery. On the other, high-volume proponents claim that more sets and reps lead to superior hypertrophy.

Both sides have strong arguments and both approaches have produced successful bodybuilders. So what is the truth? And more importantly, what is the best approach for you?

If we look at the scientific literature, we find support for both high and low training volumes. Some studies suggest that higher training volumes (more sets per muscle group per week) lead to greater hypertrophy. A meta-analysis by Schoenfeld et al. (2017) indicated a dose-response relationship between training volume and muscle growth, with more sets leading to more hypertrophy up to a point.

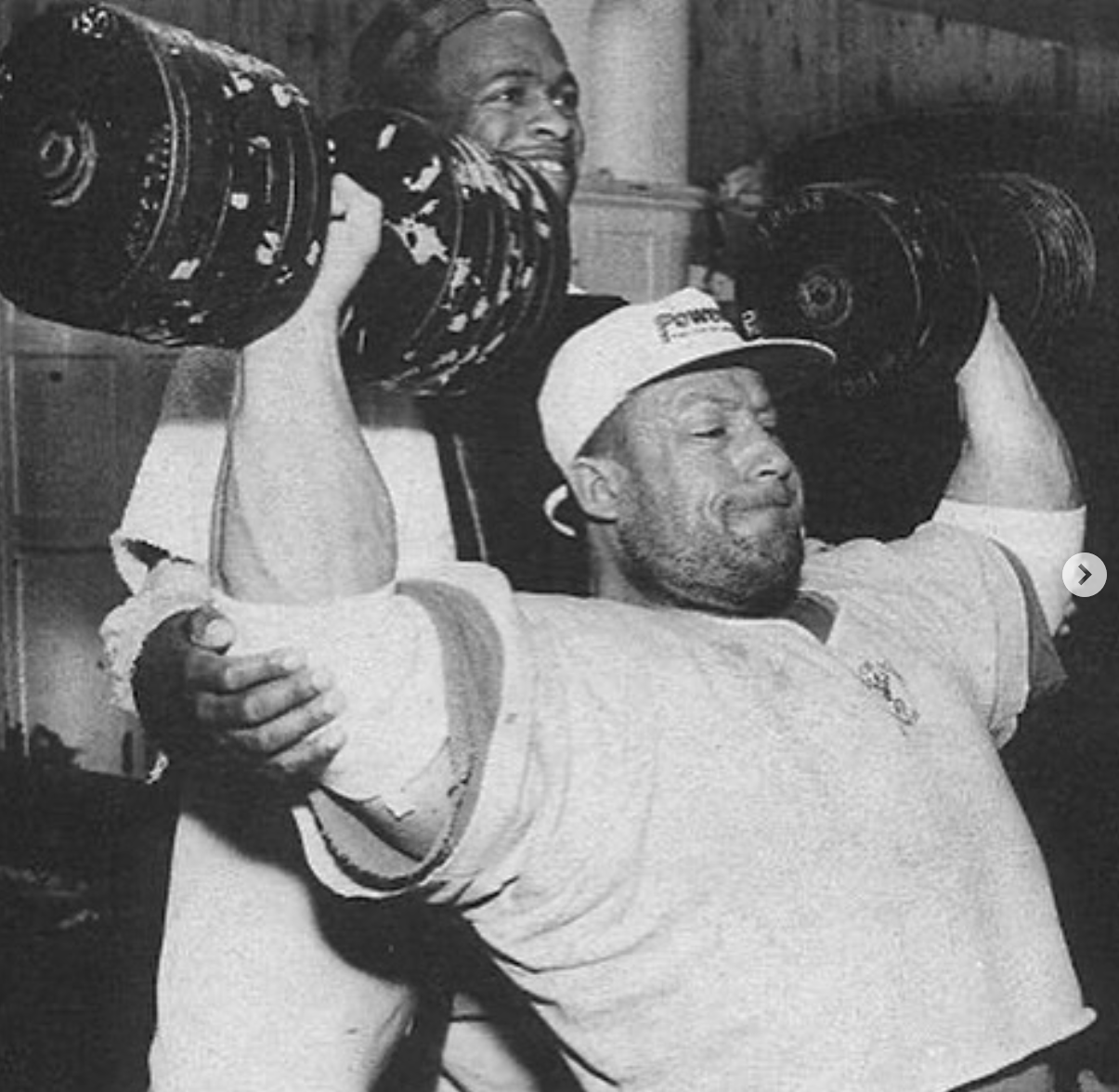

HIT training, made famous by people such as Arthur Jones, Mike Mentzer and Dorian Yates (above), focuses on maximising intensity while minimising total work. Many HIT advocates argue that anything above one or two sets to failure is not only unnecessary but that additional sets could impede progress. Studies such as those by Fisher et al. (2013) suggest that lower volumes, when performed with high intensity, can be equally effective for hypertrophy.

Surely, science can give us a definitive answer? Well, it's complicated and, when you begin to critically analyse studies by considering factors like those listed below, you can decide how much stock you might want to put into a study in terms of any conclusions you might draw. In other words, you have to get into the details.

How many subjects were in the study?

Have other studies produced similar results?

Were the subjects trained or untrained?

How advanced were the subjects?

Were they male or female?

Were they natural or assisted?

How old were the subjects?

How long was the study?

Were the subjects exposed to both conditions?

Was the study performed on all body parts or just on specific body parts?

Were the scientists taking measurements blinded?

As you can see, there are lots of things to consider that could make the findings of any study more or less relevant to you as an individual. Also, can you imagine all the uncontrollable variables involved, such as sleep quantity and quality, stress and nutrition? Do you think they might affect the results? You bet they would.

If we examine the routines of the most successful Olympia competitors, we see a range of approaches. Dorian Yates, for example, built his huge, dense physique on low-volume, high-intensity training, performing only a few all-out sets to failure per workout. In contrast, Jay Cutler (above) thrived on high-volume training without training to failure.

This tells us two things:

1) Both approaches can work – There is no single formula for success.

2) Individual factors play a huge role – Genetics, recovery capacity, training experience and even personality type (some people prefer to go all-out on their sets).

Given the fact we can observe results to support both low-volume and high-volume training, a one-size-fits-all prescription for training volume is unrealistic. Research and coaching experience both indicate significant individual variability.

A useful framework is the concept of Minimum Effective Volume (MEV) and Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV), which Dr. Mike Israetel and his colleagues introduced. MEV is the least amount of work required to make progress, while MRV is the most volume an individual can handle before recovery and performance decline. The goal should be to train within this range, gradually adjusting volume if needed while monitoring recovery.

Regardless of volume, progressive tension overload remains a key driver of hypertrophy. A lower-volume approach can be highly effective if intensity and progression are prioritised. On the other hand, higher volumes without sufficient effort and progression will yield suboptimal results. This highlights the importance of effort and execution in training. In other words, two all-out sets executed accurately to failure will probably be more effective than five lazy "fluff and pump" sets.

We know that proximity to failure is important, with each rep closer to failure being more effective but also more fatiguing. This hints at there being a sweet spot. Intensity and volume are inversely proportionate. Put another way, you can't sprint a marathon.

Some people seem to thrive on higher volumes, while others find it leads to excessive fatigue. Factors such as sleep, stress, nutrition and genetics all influence volume tolerance. Instead of mindlessly following a set prescription, we should all experiment and adjust based on recovery, performance and progress.

Even within an individual, different muscle groups may have varying volume requirements. For example, some might find that their quads require fewer sets to grow, while their shoulders or biceps seem to need more volume to grow. Adjusting training volume based on performance feedback, such as soreness, recovery time and progression in strength, allows for a more tailored and effective approach to hypertrophy. Understanding these nuances allows for better individualisation of volume across different body parts, rather than applying a uniform approach.

More is not always better. While increasing volume might enhance hypertrophy to a point, excessive volume often leads to signs of overtraining, such as joint pain, plateaus or reductions in strength, increased fatigue, less growth and prolonged recovery times. There is a balance between stimulus and recovery that must be respected, as well as how much training we can practically fit into our schedules.

The reality is that both high and low-volume training can be effective and the optimal approach depends on the individual. Instead of engaging in dogmatic debates, the best course of action is to experiment, track results and adjust accordingly. By understanding the principles of volume, intensity and recovery, we can tailor our training for maximum growth. In the end, the best training volume is not dictated by science or tradition alone but by what allows consistent progress over time.

About the Author

Alan Carson is a competitive bodybuilder and certified sports nutritionist based in Worcestershire. Competing since 2014, Alan secured the PCA British Masters Over 40s title in 2023 after returning to the stage following a four-year break. Alan works closely with a select number of clients, blending his expertise in nutrition, bodybuilding training and psychological aspects to help them reach peak potential both physically and mentally. With a passion for transformation, he's dedicated to helping clients improve their health, performance and physiques.

Read Alan Carson's previous columns HERE.

Leave a Reply