By Gary Chappell

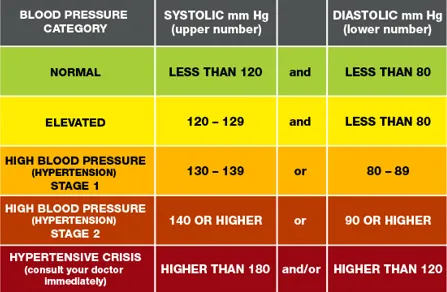

WE ARE told 120/80 mmHg represents normal blood pressure with anything significantly above that labelled hypertension.

Yet many people in the UK, especially men over 40, report being told something very different in real life. In fact, frontdouble.com has been told that paramedics see 150/90 as "normal".

So which version is correct? And more importantly, are modern blood-pressure targets unintentionally creating anxiety in people who may never realistically sit at 120/80 again?

Blood pressure guidelines tightened significantly over the past decade. Large trials such as SPRINT suggested that targeting lower systolic blood pressure (about 120 mmHg) in higher-risk populations, reduced cardiovascular events compared with higher targets.

That influenced global guidance and shifted public messaging toward lower “optimal” numbers.

But consider this. SPRINT:

It was not a study of healthy, active middle-aged adults trying to stay within a textbook ideal. And this is where a now-global problem has manifested.

Systolic pressure naturally rises over time due to structural changes in blood vessels. For many adults over 45, particularly men, maintaining a consistent 120 systolic reading is not physiologically typical.

While this does not mean high blood pressure should be ignored, it does raise a question: Are we treating natural ageing as pathology?

Guidelines are built for population-level risk reduction. This means they are largely generalised. They are designed to try to lower stroke rates, reduce heart attacks and improve long-term outcomes across millions of people.

They are not written for individualised athletic physiology, heavily muscled strength athletes and bodybuilders, or people with above-average body mass.

A 110kg resistance-trained male with elevated cardiac output and high muscle mass may not map neatly on to public health charts derived from sedentary populations. Yet the same 120/80 benchmark is applied universally.

And there is another uncomfortable layer to this; being told you are “hypertensive” when you feel well can trigger health anxiety, repeated checking, hypervigilance and stress. All of which can trigger high blood pressure. Especially in isolation.

The irony is difficult to ignore. For some individuals, constant focus on chasing 120/80 may increase sympathetic nervous system activation, potentially driving readings higher.

This does not mean high blood pressure is imaginary, but it does suggest that messaging matters.

In acute care settings, clinicians assess danger, not long-term optimisation. A stable adult at 150/90 is not in crisis or regarded as a hypertensive emergency and so does not require urgent intervention. So reassurance is given that it is not acutely dangerous.

What this means is that official guidelines may be simplified for public messaging. There is a difference between:

For some people, especially older adults, aggressively pushing systolic blood pressure down can cause dizziness, falls, reduced cerebral perfusion and lower diastolic pressure. This means that lower is not automatically better for everyone.

Let's take bodybuilders, for example. They often present with higher bodyweight, increased left ventricular mass (physiological adaptation), higher haematocrit, elevated sympathetic tone, stimulant use and sleep disruption. Their cardiovascular profile differs from sedentary populations.

So while this does not make elevated blood pressure harmless, it means it complicates blanket statements. Bodybuilders not showing 120/80 blood pressure does not mean they are suddenly a walking heart attack or stroke. And those parading such numbers on social media does not mean they are a bastion of health, either. It does mean boasting about 120/80 simply to tick a box on the "official guidelines" is likely doing more harm than good to those watching.

Instead of asking: “Is 150/90 normal?”, better questions may be:

Blood pressure is one dial on a much larger dashboard.

While 120/80 may be optimal in an "official" statistical sense, optimal is not always achievable for every adult at every age. And that does not automatically signify imminent danger.

There is a risk that simplified public messaging turns nuanced cardiovascular risk into a binary label – normal versus abnormal – creating unnecessary worry.

The goal should not be chasing a single number. The goal should be understanding risk and reducing it intelligently.

Leave a Reply